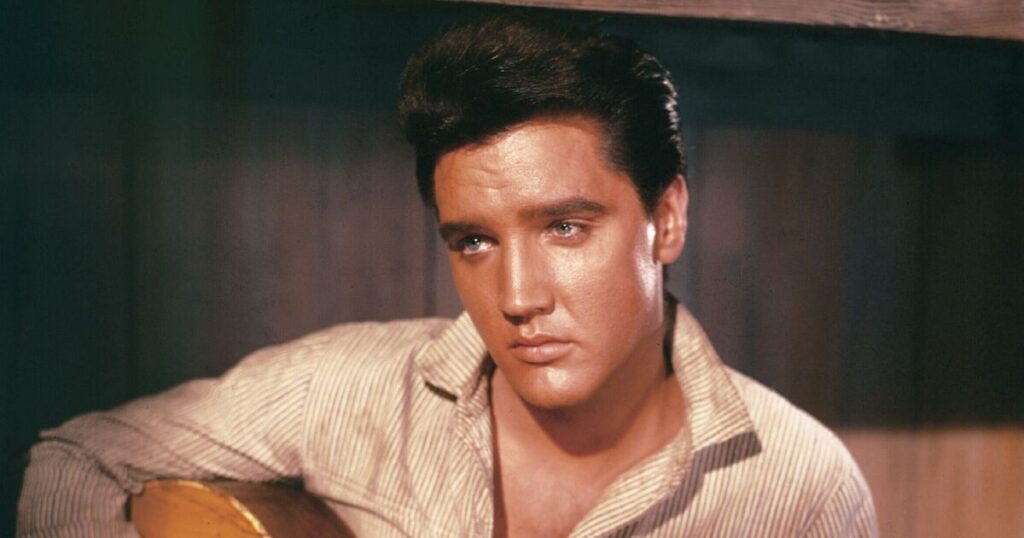

Elvis Presley is a name synonymous with rock and roll, a cultural icon whose unmistakeable voice and ahead-of-its-time performances sparked a musical revolution back in the ’50s.

To his millions of fans, Elvis was the groundbreaking artist who brought a new sound into the mainstream, blending rhythm and blues with country to create a genre-defying style.

While some celebrate him as a revolutionary who bridged the gap between genres that were deemed inherently black or white in racially-torn America, others argue that his success came at the expense of black artists whose contributions to rock ’n’ roll were overlooked and underappreciated.

Some context first: Born in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935, Elvis grew up in poverty in a predominantly black neighbourhood. From a young age, he was immersed in gospel, blues, and rhythm and blues – the music of Black churches and juke joints that shaped his distinctive style.

When his family moved to Memphis, Tennessee, Elvis’s exposure to Black musicians deepened even further. He would frequent Beale Street, the heart of the city’s music scene, where he forged friendships with blues legends like B.B. King.

Many of the songs that helped launch Elvis’s career – ‘Hound Dog’, ‘That’s All Right’, and ‘Mystery Train’ – were originally recorded by Black artists. His early records for Sun Records introduced a raw, energetic sound that fused country with rhythm and blues, a blend that would soon electrify American audiences. Yet from the beginning, controversy followed.

Elvis was often described as a white man who “sounded Black,” and his provocative performance style – marked by swiveling hips and dances – was unlike anything most white audiences had seen. His televised performances caused a national stir, earning him the nickname “Elvis the Pelvis” and drawing criticism from conservative commentators. But while his stage presence shocked some, it thrilled millions of young fans and cemented his status as a cultural icon.

However, Elvis’s success has always raised questions about cultural appropriation. Many of the songs that became hits for him had previously failed to gain mainstream traction when performed by Black artists. Big Mama Thornton’s original version of Hound Dog, for example, was a blues classic, but it was Presley’s cover that topped the charts. For some critics, this is emblematic of a music industry that systematically favoured white performers while sidelining the Black pioneers who created the genre.

Public Enemy’s Chuck D famously criticized Elvis in the 1989 song ‘Fight the Power’, rapping: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant s*** to me… Straight-up racist, that sucker was simple and plain.” While Chuck D later clarified that his criticism was directed more at the music industry’s systemic racism than at Elvis personally, the comment highlighted a long-running debate about appropriation versus appreciation.

Musicologist Neil Kulkarni echoes this sentiment, arguing that much of pop music’s history is a story of black innovation being repackaged for white audiences. “The music industry knew there were white teenagers listening to rhythm and blues, and they were looking for a white face to market it. That’s how Elvis became the figurehead of rock ’n’ roll,” he says.

Still, not everyone sees Elvis as a symbol of exploitation. Historian Michael T. Bertrand, author of Race, Rock, and Elvis, argues that Presley’s genuine love for Black music helped break down racial barriers in a segregated society.

“Elvis represented a generation that grew up listening to Black radio programming in the late 1940s,” Bertrand explains. “He had an appreciation of African-American culture that was rare for white southerners of his time. By performing Black music, Elvis helped some white audiences rethink their attitudes about race.”

Many Black artists, including B.B. King, saw Elvis as a friend and ally. King once said, “I don’t think Elvis ever thought of himself as the King of Rock ’n’ Roll. He was humble and respectful. He knew where the music came from and gave credit when it was due.”

Elvis also showed support for Black causes in quieter ways. In 1956, he attended the WDIA Goodwill Revue in Memphis – a benefit concert organized by a Black radio station to raise money for underprivileged children. Though his contract prevented him from performing, his presence at the event spoke volumes to those in attendance.

Despite his ties to Black music, Elvis rarely made public statements about civil rights. Some argue that this was a missed opportunity for a figure of his stature. Others suggest that his silence was the result of cautious management by his infamous manager, Colonel Tom Parker, who was determined to avoid controversy that might hurt Elvis’s commercial success.

Whether Elvis was a cultural bridge or a symbol of appropriation remains a matter of perspective. What’s undeniable is his lasting impact on music and popular culture. He helped introduce Black-inspired music to a global audience, even as many of the original artists struggled for recognition.